Introduction Q&A

Introduction Q&A

What is an early formative experience?

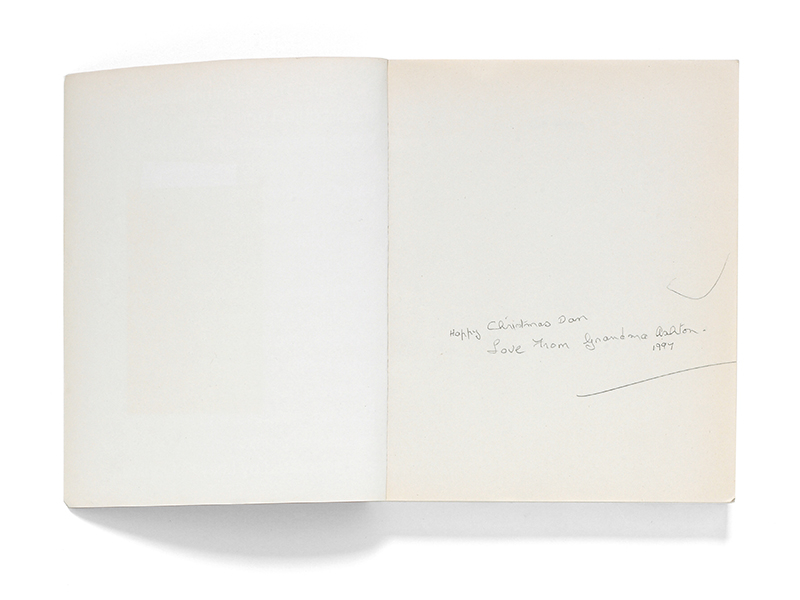

At age eighteen I discovered a book called Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object by Lucy Lippard. To me this book reconfirmed that a concept can be equally as beautiful as its aesthetics. I was so excited that I read it too quickly, not fully appreciating its content, and had to read it again. Following a Christmas tradition, my grandmother would ask my mother to buy a present for her to give to me on Christmas morning. My Mum later passed the task to me, so I bought a reissue of Six Years, which my grandmother then gave back to me on Christmas morning. I acted surprised, as promised, when unwrapping it. “Thank you, Grandma. A book on the dematerialization of the art object, just what I always wanted.” She wrote a note on the inside front cover, and I treasure it over all other books. Six Years made me realize that art and design were no longer disciplines that were motivated purely by aesthetics. I wanted to relate Lippard’s ideas of dematerialization to graphic design, exploring objectivity, systems, and concepts, and remove as many aesthetic decisions from the design process as possible. I asked myself whether graphic design can be dematerialized, or whether the graphic can be informed by a concept.

You feature lots of works from other people on this website, do you like to collaborate?

I like participatory projects. I like to make invitations and display the results. One of these projects is Thank You Pictures, which originally started as part of Picture of the Week, a single image displayed on my homepage that changes each week. I began Picture of the Week with an open invitation for others to contribute, and each week I would update the site and add the previous image to the archive. After three years I decided to separate the contributions from my own pictures, resulting in two projects: Thank You Pictures, submissions e-mailed to me (usually from people I have never met) and Picture of the Week, my own pictures. Both projects share the same concept, presenting incidents, alignments, coincidences, viewpoints, temporary situations, and other small things that often go unnoticed. The pictures are conceptual observations and not photography. The image is not as important as the content, and the title is as much a part of the work as the photograph. These two projects have slowly evolved into a major part of my practice, infiltrating my everyday life and affecting my gaze and the way I appreciate the moment.

How do you use your own website?

My website has evolved into an open space where I feel very comfortable publishing projects ranging from unfinished works and quick ideas, to commissioned works, invitations, and submissions from others. It acts almost like a box where the most recent project is at the top and the oldest one at the bottom. This chronology helps me keep track of when things happened and enables viewers to dip in to the index list and exhibit area and browse projects at will, breaking with chronology, revealing connections and recurring themes within works.

Were you creative as a child?

In primary school I was the best at drawing. My teacher, Mr. Bencley, called me Little Picasso, and I won all the drawing competitions and spent a lot of time making pictures. At high school, I was second best. Dan Forster was much better. He could draw intuitively. I remember watching him draw from a plaster cast replica of Michelangelo’s David and later, during a vacation we took together in the south of France, I saw him make amazing pen drawings on the beach. I am competitive, and since I knew I could not compete with Dan’s drawing ability, I understood that to be happy, I had to invent a creative way around the problem of making things look beautiful. So while Dan was drawing perfect renderings of the beach, I drew two straight lines on a page, dividing it into thirds. I wrote “sky” in the top third, “sea” in the second, and “sand” in the bottom third. I realised in that instance that the craft and skill of drawing can be overcome with an idea. This simple realisation has changed the way I approach almost everything I make. If something does not come naturally, I search out an alternative way to respond to the problem.

What were you like as a college student?

During my time at Ravensbourne College of Design and Communication in London I always arrived early for lectures and sat at the front. I tried hard to antagonize people with an unwavering commitment to my work. It felt punk rock to be the hardest working—a reversal of the cliché slacker student. I enjoyed provoking by being on time, having a well-thought-through solution to the brief that broke with the statuesque, and working when others were at parties.

Are you the same now?

I think I’m a bit less intense now. I still like to arrive on time and enjoy breaking with the statuesque, but feel more relaxed, and enjoy the things I do the more I do them.

What is your favourite colour?

During my time at the Royal College of Art I adopted grey as my favourite colour, because it felt neutral, a mid-way between black and white. I still like grey, but think it’s a bit pathetic to claim it as a favourite colour, as it lacks passion. So I embraced the most archetypal favourite colour: bright red. It always goes well with black, white, or grey. Recently, I have been drawn to bright green, the exact opposite of bright red, its complementary colour. I often change my mind and do a complete reversal.

Can you summarise in a couple of paragraphs the key moments that affected your practice?

At age eighteen I started at Ravensbourne College in London, studying communication design, and had an amazing first year being taught by Rupert Basset, Collin Maughan, and Geoff White. They gave me a rigorous back-to-basics Bauhaus Swiss modernist induction to design. I graduated in 1996 and went on to study for a further two years at London’s Royal College of Art. A few months before graduation, Rick Poynor, one of my teachers there, suggested I look into an internship at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. When I went to visit the Walker Art Center, I met the new design director, Andrew Blauvelt, and felt immediately inspired and committed to working there. I had an interview, got the job, and started in November 1998. I worked almost twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, for just over a year. During this time I became friends with Sam Solhaug, who worked on the exhibition crew and with whom I collaborated on my first piece of furniture. In one of our conversations about art and design I mentioned an idea to cut an eight-by-four-foot sheet of one-inch plywood into one-inch strips, turn them all ninety degrees, and laminate them back together with the plies running vertically through the sheet. Sam suggested to also form legs from the plywood, transforming the idea from creating a plywood sheet turned inside out to producing a functional table based on the same concept. After stipulating that there should be no material waste, we independently drew identical cutting patterns and designed the same table. We worked for a few weeks after hours in the Walker’s carpentry shop to build a prototype and decided to present it at the Milan Furniture Fair. I returned to London at the end of 1999 and started teaching two-and-a-half days a week as the third-year graphic design tutor at Brighton University. I also found a studio space in Bethnal Green to pursue my own projects. In February 2000 Sam visited, and we spent three weeks working in Pentagram’s carpentry shop (thank you Angus) to build a perfect 10.2 Multi Ply Coffee Table for the Milan Furniture Fair 2000. Together we decided to call our informal collaboration Foundation 33, inspired partly by a recent trip to Marfa, Texas, where the many Donald Judd buildings displayed “Judd Foundation” in bright red capital letters in their windows.

In Milan we met Lyn Winter, who for a 15 percent commission of sales offered to promote and find retail outlets for the 10.2 Multi Ply Coffee Table and future projects. Once back in London Lyn visited my studio and discovered that I was a jack-of-all-trades, not a furniture designer as she had first expected. So she introduced me to her friend Katie Hayes, who worked in the marketing department at Channel 4 Television. The first time I met Katie she was wearing a white jumper with two red cherries embroidered on each side. I showed her my projects, and a week later she invited me to pitch for the design of an identity for a new series of the megahit program Big Brother. After finding out there were another eight, much more established, design studios pitching for the job, I felt like the underdog. I spent two weeks working for the pitch, at the end of which I asked my close friend Tim for feedback. He said I had created something that I felt Channel 4 wanted, rather than following my own judgment. I knew he was right, so I started from scratch. In the following two days I made a very quick and direct ideas pitch, had a memorable meeting, and won the project.

Do you stick to the brief when working on a commissioned project?

I have always been interested in embracing restrictions, in making the most out of what you have. I like challenges, such as “who can build the tallest structure out of ten sheets of A4 paper.” I like set parameters to work within. In graphic design there is usually a defined medium or message, and it’s the designer’s role to push and challenge the restrictions to create something that communicates. My enjoyment comes at challenging the givens. In Formula 1 races, teams are always on the edge of breaking the rules. The weight of the cars and drivers is so close to the allowed minimum that after each race on the slow-down lap, drivers drive on the outer edge of the circuit so that the hot sticky tires collect discarded tire rubber and gravel to add extra weight to the cars before they are weighed.

What is your favourite project?

This website.

To what questions would you like to know the answer?

What is the heaviest material in the world that is safe to sculpt with—i.e., non-radioactive—and what would the circumference be of a sphere using a ton of this material? Do Day-Glo colours have complementary colours? Is it possible to make an audio recording of a sonic boom? Why do people smoke?

What things irritate you?

People who copy, smoke and drop litter. The list goes on and on. Refer to the No Manifesto.

How controlling are you when working on projects?

My favourite works are the ones where control has been relinquished. I like setting up frameworks from which the project can then evolve. For instance, I am fascinated by just how many varieties of No Smoking signs exist. I am collecting as many versions as possible to add to my online No Smoking Sign Library, where EPS files for each featured sign can be downloaded and used for free. I invite everybody to draw a No Smoking sign to be added to the library. To contribute, e-mail a vector EPS graphic that fits within a one hundred millimeter square, using red and black only, to daniel at eatock dot com.

Are you against graphic design?

I never liked the term “graphic”; it suggests the surface, while I always prefer what is underneath the surface. I try to avoid subjective decision making, decoration, and unnecessary graphics. I like ideas and concepts that inform or dictate the aesthetic. I prefer the idea to stand out rather than the aesthetics, the content to stand out rather than its display.

Do you like miscommunication?

A few years ago I was featured in the New York Times. I was so excited that I asked my girlfriend Flávia, who was living in the States, to get me ten issues. She asked me why I wanted tennis shoes. I explained that I wanted to give them to friends and family. It took us both a few seconds to see the miscommunication. Recently, my sister asked for a pineapple juice in a bar and was given a pint of apple juice. And when she was a kid, I heard her shout to my Mum and Dad to switch the dark off. Another time, when I was rebuilding some metal shelving, she asked if I was “mantleing” them, since I had previously dismantled them. I really love miscommunication, or an opposite/sideways look at something.

What tools do you use?

I once received an e-mail from a stranger who described my work as being made by a brain rather than a paintbrush. The brain is the most democratic tool that all artists and designers share.

What is your obsession?

I like to draw circles freehand on A4 sheets of paper. At one time in my studio I had over twenty-five thousand sheets of paper in piles, each with a hand drawn circle. My favourite part was the join—how accurately the two end points meet. My obsession is to find sense in nonsense and nonsense in sense.

So you’re obsessed by making circles?

I like circular ideas, like a dog chasing its own tail, or taking a photograph of the strap attached to your camera. Occasionally, the camera strap sneaks into a picture by mistake, swinging innocently in front of the lens and distracting the attention from the intended subject. Camera Strap Photos, a project I started in 2004, on the other hand, are not mistakes. I invited people to intentionally place the straps in the picture. Each photograph presents an alternative: the backdrop to the camera strap now becomes a secondary subject.

What do you hope to design someday?

I hope to discover/invent/design an archetype—something that is so great that it becomes almost invisible, something that people use all over the world and take for granted.

What do you do when you’re not working?

Sleep.

Do you watch television?

No but I do remember two very memorable television programs from my childhood. The first one is Wide Awake Club, broadcast on Saturday mornings. The presenter Timmy Mallett played “Mallett’s Mallet,” a word association game in which contestants weren’t allowed to pause, hesitate, or repeat a word or they would get bashed on the head with a large pink rubber mallet. The second is Crackerjack, a British children’s comedy BBC television series. The most interesting game of the show was a quiz called “Double or Drop.” Children were picked from the audience to answer questions while holding on to an ever increasing pile of objects, winning prizes for a right answer and cabbages for a wrong one. They were out of the game if they dropped any of the items.

Tell me about your fascination for blank spaces.

I have an aversion to filling out forms, but I became fascinated with the idea of using instructions and blank spaces as an opportunity for people to complete my work. This goes back to my drawing of the beach: there is a lot of blank space asking the viewer to use his or her imagination. Not filling something in gives more potential to the reader to participate. I always prefer reading or listening to music to watching a film. I think that films give too much away—they are very descriptive, whereas reading or listening to music sets my imagination working.

Where and when were you born?

Bolton, England. 18 July 1975.

What was the fastest lap time around the Three Sisters Race Circuit?

50.24 seconds.

What gear ratio is your fixed-wheel bike?

42/22

Are there any questions that I have not asked that I should have asked?

Are you good at telling jokes? What is the best part of life? Who is your biggest inspiration? What was your most embarrassing moment? What was your first car? Who is your favourite Formula 1 driver? Do you have any secrets? What is your favourite fruit? How quickly can you recite the alphabet? If you could have a wish come true, what would you wish? Which musicians would you put together to form the ultimate band? Would you prefer to be run over by a steam roller or jump off the Empire State Building? Which is the fiercest animal? What is your favourite animal? Do you have any tattoos? What came first, the chicken or the egg? Who was faster, Ayrton Senner or Michael Schumacher? Would you take a time machine back in time or into the future?

Who would you most like to interview?

Andy Warhol.

Why did you do an interview with yourself for your website?

I wanted to include an informal, conversational addition to the works, providing references, memories, key stories, and thoughts that are of equal importance as the projects themselves, and I wanted to keep the content 100 percent homemade.

Interview by Daniel Eatock with Daniel Eatock

August 2007 (updated/edited May 2019)